Since my post on passive lighting got a little unwieldy (900+ words! Who has time for that?) I decided to break this post in two in hopes of avoiding another monster post. So today I’ll be covering passive heating from the perspective of what should be done before or during construction of a building.

I know, I know, it’s the beginning of July, and probably the last thing you want to think about is keeping your house warm. But it might be better to think about this sort of thing now than in the middle of January when you open your heating bill. In fact, you might still be recovering from the number those polar vortex heating bills did on your budget this past winter. So I propose that it’s always a good time to think about how you can more efficiently (and cost effectively!) heat your home.

Passive heating ultimately comes down to two goals:

- Capture heat from the sun.

- Seal up your building so the heat doesn’t escape.

Just like with passive lighting, before construction begins is the best time to start thinking about passive heating. Some forethought on position and building materials can save all sorts of heat energy down the line.

Siting

The goal when siting a building for passive heating is to put the broad side of the building in direct sunlight. Here in the northern hemisphere, that means the south side of the building should be the broadest side. The west side is also a good choice because the afternoon sun is stronger and hotter than the morning sun.

Windows, Walls, and Floors, oh my

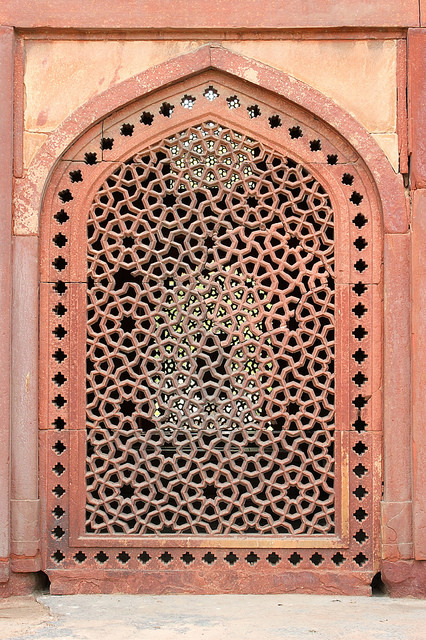

So, now that you’ve set up the position of your building to soak up the sun, you need to get that heat from the outside in. This can be done by putting nice big windows on the sunny side of your building. Some types of window glass are better at allowing heat to pass through them than others. For passive heating, look for a solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) of 0.6 or higher.

And once the heat is inside, you want to hold it there. Flooring and wall materials such as concrete and tile are great at holding onto heat (this is called a solar mass). So put a tile flour under your big southern window. And build that southern wall with bricks or concrete blocks.

Side note: In our neighborhood in Detroit, we often saw that flowers planted beside a brick building were among the first to pop up in the spring – the bricks held onto enough solar heat to convince those seeds to germinate a bit earlier!

Insulation

Insulate. Insulate. Insulate.

Insulate more than the minimum recommendation. Insulate on the outside of the thermal mass (because you want to keep that heat inside!). Remember, heat rises and wants to dissipate into cold air, so insulate your roof especially well, and your north wall too.

So there you have it, three main areas of consideration when it comes to construction and passive heating. If you’re planning on getting your house re-roofed this summer, take some extra time to check the quality of your roof insulation, and add some more!

…

Are you looking for an introduction to passive design? You can find it here.

Oh, hey, Building Earth has a facebook page now. Keep up to date on posts and other interesting green news by liking us!